General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)

When we start working out, the first thing we do is figure out a training plan to follow for the next few weeks or months.

This plan (hopefully) follows a proper structure of periodization that provides a framework for success when training.

This is so that training tasks and workloads are “varied at a multitude of levels in a logical pattern in order to ensure the development of specific physiological and performance outcomes at predetermined time points”.

In simpler terms, periodization is the planned manipulation of training variables (load, sets, and reps) in order to maximize training adaptations and to prevent the onset of overtraining.

To understand how periodization manages the recovery and adaptive responses in the body, we’re gonna talk about one of the fundamental mechanisms of exercise physiology – The General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS).

The general adaptive syndrome (GAS) is one of the foundational theories from which the concept of periodization of training was developed.

It was first developed in 1956 by Hans Selye, and describes the body's specific response to stress, either physical or emotional.

General adaptation syndrome (GAS) describes the process your body goes through when you are exposed to any kind of stress, positive or negative.

It has three stages: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

While the GAS does not explain all the responses to stress, it does offer a potential model that explains the adaptive responses to a training stimulus.

The most important factor of the GAS and periodization revolves around stress.

These stressors are defined as anything that causes stress or elicits the stress response.

Stress will disrupt homeostasis and this leads to an adaptive response.

Homeostasis is defined as the ability of the body to maintain a stable internal environment for cells by closely regulating various critical variables such as pH, acid-base balance, oxygen tension, blood glucose concentration and body temperature.

Exercise and physical training are biological stressors and the body reacts similarly to exercise as it does to other stressors.

One of the most basic forms of stress in exercise is when we lift weights.

If we bicep curl a dumbbell, this creates a disturbance in homeostasis and stimulates a response to that stress.

Ultimately, the muscle recovers and generates a little more muscle to compensate for the workload next time we lift.

Basic stuff, eh?

Now, there are 3 phases of stressors.

- Acute phase – homeostatic adjustment (alarm reaction)

- Chronic phase – stressors accommodated by adaptations (stage of resistance)

- Exhaustion phase – maladaptations occur (state of exhaustion)

Additionally, there’s more than just the stressor of exercise. Other stressors include:

- Exercise

- Food deprivation

- Hypo- or hyperthermia

- Psychological challenges

- Social challenges

- Environmental factors

- Etc.

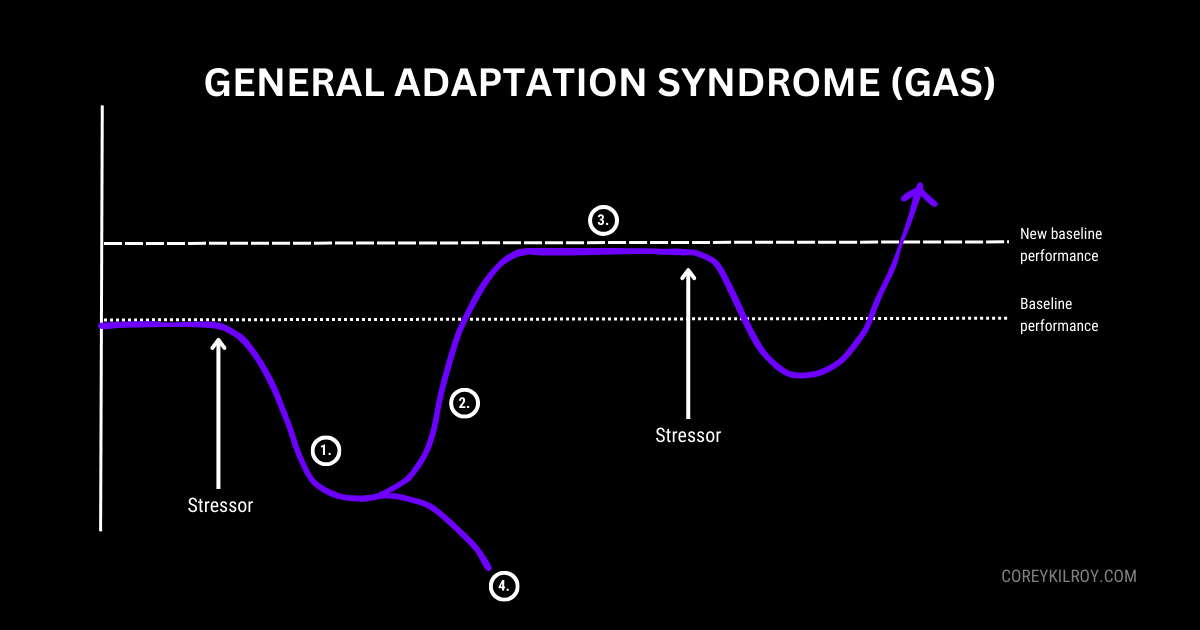

The diagram below will further illustrate the GAS response to these stressors.

- Alarm Phase: Initial phase of training when stimulus is first recognized & performance generally decreases in response to fatigue.

- Resistance Phase: The 2nd phase in which adaptation occurs & the system is returned to baseline or in most instances elevated above baseline.

- Supercompensation Phase: New level of performance capacity that occurs in response to the adaptive response found in step 2.Overtraining Phase: If stressors are too high, performance can be further suppressed & overtraining can result.

- Overtraining Phase: if stressors are too high, performance can be further suppressed & overtraining can result.

When a training stress is introduced (i.e. a bout of exercise, etc.), the initial response, or alarm phase, reduces our performance as a result of accumulated fatigue, soreness, stiffness, and a reduction in energy stores. The alarm phase initiates the adaptive responses that are central to the resistance phase of the GAS.

If the training stressors are not excessive and are planned appropriately, adaptive responses will occur during the resistance phase.

This resistance phase is when our body adapts to the stressor and performance will be either returned to baseline or elevated to new higher levels (supercompensation).

Conversely, if the training stress is excessive, performance will be further reduced in response to the athlete's inability to adapt to the training stress, resulting in what is considered to be an overtraining response.

It’s also important to realize that all stressors are additive and that factors external to the training program (e.g., interpersonal relationships, nutrition, and career stress) can impact the athlete's ability to adapt to the stressors introduced by the training program.

To sum it all up, when our body undergoes a physical or emotional stressor (i.e. resistance training, emotional stress, etc.), our bodies are unaccustomed to this. This results in a physiological response to adapt to the stressor so we’re better prepared for that stressor in the future.

This creates a new baseline level of fitness that’s higher than previously.

Our goal is to continue to increase this level through proper training and periodization.

Recovery plays a major role in this as well, which allows our bodies to recoup and initiate that adaptation.

In the end…

The training program you’ve acquired is (hopefully) set up in a way to induce this Generalized Adaptation Syndrome (GAS).

This will not only ensure that you’re progressing in your training but working efficiently as well.

Running the same pace or lifting the same weights every day won’t get us anywhere without progressive intensity and volume.

Now get to work.

Good luck & Keep Pluggin’.

🙇🏻♂️🌱 Until Next Time, C.